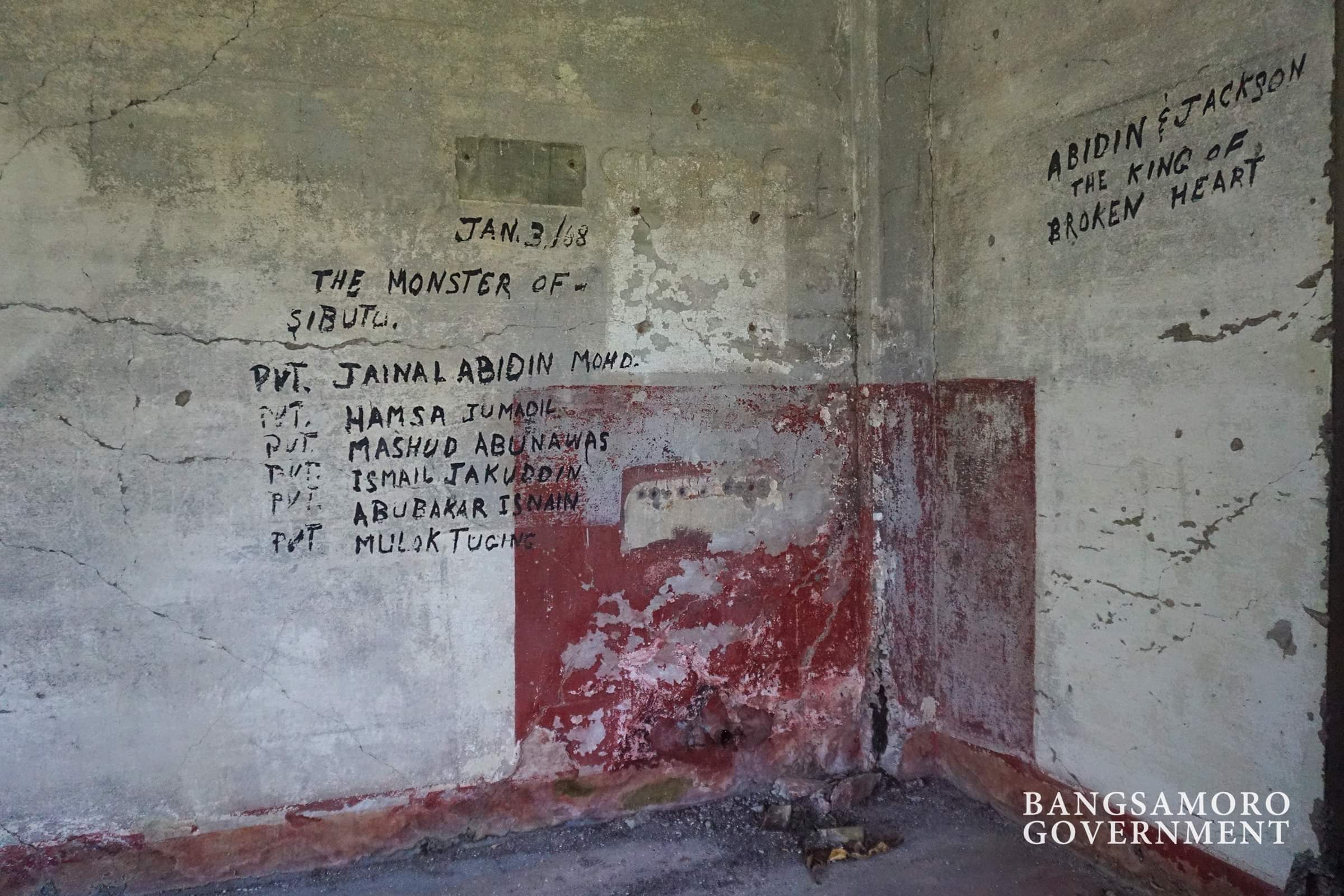

Names of some members of the Jabidah unit can still be seen on the walls of the old hospital in Corregidor Island where the young Moros were housed.

Fifty-three (53) years ago, the tragic incident that lit the spark of the decades-long Moro rebellion in Mindanao took place.

Five decades later, the Jabidah Massacre continues to linger in the memories of Moro revolutionaries and its leaders.

Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) Chairman Muslimin G. Sema and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) Peace Implementing Panel Chair Mohagher M. Iqbal shared their stories on how the 1960’s Moro insurgency became an eye-opener and its relevance up to the present.

According to them, the story of Jibin Arula, who was the lone survivor from the Corregidor carnage happened on March 18, 1968, triggered the creation of former Cotabato Governor Datu Udtog Matalam’s group—the Muslim Independence Movement (MIM)— which was a result of the ardent feeling and unity of Moro intellectuals.

“When we heard that Jibin Arula was brought to Governor Montanio of Cavite, pumunta kami nina Prof. Nur Misuari, Abul Khayr Alonto, and Utto Salahudin para malaman ang totoong nangyari […] when the problem was divulged, we demanded justice; we petitioned to Malacañang, Congress to demand an investigation,” Sema recounted.

According to Sema, when they felt that the Marcos administration seemed to cover up the incident, they automatically conducted rallies in front of Malacañang palace.

“Nagkaroon kami ng vigil for ten days at ten nights, calling Marcos to address an investigation, but there was no effort to do that. Spontaneous demonstrations happened in Zamboanga, Sulu, Marawi, and other Muslim communities as part of the effort to seek justice,“ he added.

Later, several Moro separatist movements were founded, including Cong. Rashid Lucman’s Bangsamoro Liberation Organization (BMLO), and eventually, Misuari’s MNLF.

Jabidah kept on happening

The Jabidah massacre may have occurred in a specific time, but far from the consciousness of the many, Jabidah has been happening long time ago. Moros’ resistance against foreign subjugation has been there since the Spanish rule up to the time of American rule.

Iqbal often asked during their negotiation times with the government, “bakit tayo nagiging problema? Samantala ay atin ang Mindanao; dito nagpakamatay ang mga ninuno natin at nilabanan ang lahat ng pumunta dito [mga Kastila, American, Hapon at pati British], nilabanan natin silang lahat. Bakit tayo nagiging problema?”

Some of the significant historical injustices were the Bud Dajo massacre, Manili massacre, Ilaga terror, and so on. In the later years, the Moro struggle continued not just in the battlefield, but also on the peace negotiating table.

Iqbal said, “for years iyon ang pinag-usapan kung papaano ma-resolve ang problema ng Moro”, mentioning the several significant events prior to the establishment of Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) such as the Comprehensive Agreement for Bangsamoro (CAB), Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL), and the Normalization process.

Iqbal recalled his years of experience, fighting for the right to self-determination in the Moro land. He asserted, “we [must] continue to assert and to exercise our right to self-determination.”

Preserving the struggle

Today, Jabidah has become a symbol of injustice as well as a wake-up call for the Bangsamoro.

For Sema, to preserve the struggle, the Moro nation should always look back to the past.

“We must not take off our eyes and our memory to the past and what is happening right now,” he stressed.

“We have to always assess what is still lacking, and we have to scientifically examine what we have suffered; what we have missed; what is not there yet; and what is still needed,” Sema said.

Meanwhile, Iqbal, who is also the author of the book ‘Bangsamoro Under Endless Tyranny’, stressed the importance of knowing the history.

“Mahalaga na gunitain natin ito (Jabidah Massacre); it is a wake-up call for us. Importante na alam natin ang nakaraan, upang maintindihan natin ang kasalukuyan, sa ganitong paraan natin malalaman ang maaaring mangyayari sa kinabukasan,” he said.

“We have to separate facts from fiction; we have to correct history—the history of the Moro people is longer than Philippine history,” he added. (Bangsamoro Information Office)

![]()